|

| 'Longwood' the Haller Nutt House, Natchez, MS. 1859 Photo: Wikimedia |

'Longwood' is perhaps Sloan's most famous commission, his most eccentric, and his greatest unrealized project. Dr. Haller Nutt, a wealthy planter and agricultural inventor, commissioned Sloan to design the house in 1859, and by 1861, the exterior was completed. The outbreak of the Civil War, however, caused the workmen from Philadelphia to abandon the project and return north. The house was left with a finished exterior, but an unfinished interior, with only the basement complete and the remainder framed. The house suffered neglect, as Nutt lost most of his wealth during the war, but has been restored as a tourist venue. As a unique survival, Longwood provides us with a wealth of information on the process of construction and framing in the 19th century, an ironic testament to the work of Sloan as a pioneer of balloon framing. Additionally, the house is one of the most important and well known monuments of

Indian Italianate in the US.

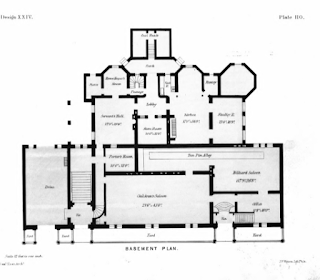

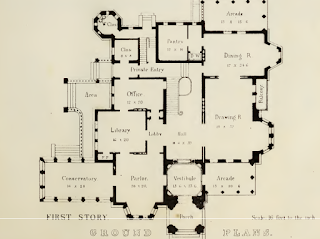

Sloan's design for the house, an octagon, was based on the briefly popular octagon shape popularized by Orson Quire Fowler, a lifestyle theorist in the 19th century who theorized that the octagon shape was more healthful and economical, leading to a spate of houses based on Fowler's designs. The plan that Sloan selected as the basis of Longwood was published in the

Model Architect v.2 in 1852 as an "Oriental Villa". It remains one of the most elaborate examples of the fanciful strain of Indian Italianate design in the US, but, like the style in general, it remains Italianate to the core with a spattering of oriental details and design elements.

The original design:

The plan is octagonal, but Sloan has complicated the design. Four of the facades on the first two stories project by several bays, forming a Greek cross shape; these bays alternate with double storied porches, filling out the octagon shape. Each façade on these first two stories has three arched windows; on the projecting facades, these are closely spaced with a hanging porch on the first floor with three arches answering the windows. One the recessed facades, there are two windows flanking a door on each story, forming three arched openings. The third floor reverses the rhythm of projections and recesses on the first two; where the façade projects on the first two stories, it recedes on the third and vice versa. The fourth floor abandons the triple arched motif in favor of paired tombstone windows, a typical Sloan maneuver to differentiate the third floor. The whole is topped by a tall polygonal drum with arched windows and an onion dome, the consummate Indian/Mughal design element.

As much as the house makes a pretense of Indian design features, it doesn't nearly capture the authenticity of Henry Austin's Indian houses in New Haven, such as the employment of candelabra columns. Rather, it uses primarily vernacular Italianate motifs, but arranges them in such a way as to suggest the oriental world. For instance, a look at the double story porches shows Corinthian columns (of a slightly lusher variety than a strictly classical design), but the scrollwork on the porch is designed to mimic the horseshoe arches and ogee shapes in Islamic architecture. Horseshoe arches can also be found on the balustrades. On the side balconies, we see horse shoe arches again with interesting moldings above the columns, a further feature that recalls the Alhambra. Finally, the fringes on every cornice line and the dome itself, which has an onion shape, pull the entire composition into the Indian mode. One bizarre feature that I am at a loss to explain is the strange tracery in the windows, which looks more Chippendale gothic than Moorish.

All following photos from

Wikimedia.

Unfortunately, the interiors were never finished, but this allows us a good glimpse of the construction methods of the house: