A blog devoted to American Italianate architecture of the 19th century. This blog features architectural analyses of Italianate domestic buildings with images, and historical information. My plan is to show the varieties, regional vernacular of Italianate architecture.

Showing posts with label symmetrical plan. Show all posts

Showing posts with label symmetrical plan. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

74 W Main St. Clinton, NJ

Just a few lots down from the Bosenbury house is this interesting gem, a symmetrical plan house which is oddly five bays on the first floor and three bays on the second floor. On the first, the house is surrounded by an oddly asymmetrical porch which wraps around one side but not the other leaving us with a four bay porch that does not present a symmetrical number of bays on each side. The front door has a Greek Revival eared molding surround. On the second floor, all the windows are segmental arched with a double window in the center with a pointed molding with a vegetal anthemion above. There is an engaged open pediment above with the typical Clinton wheel window, this time with eight spokes rather than four. Oddly, the pediment is deeply enclosed by the eaves. The design unfortunately suffers from a rather odd painting decision, with the bordering boards not painted to form a unity with the entablature, which if painted the same color would make the design much clearer. The house likely dates from the 1850s-60s.

Sunday, April 8, 2018

The Thomas E. Powell House, Columbus, OH

|

The Thomas E. Powell House, Columbus, OH. 1853

Both Photos Columbus Illustrated and History of Columbus

|

Although not part of E Town Street, but part of the E Broad Street area, another mansions street in its own right, I couldn't resist this rather bizarre Italianate of 1853. The house is a symmetrical plan Italianate with a brick façade, and it's in this paneled brick style that it is most distinctive. The house is divided by its brickwork into three bays by pilasters topped with moldings. The side bays enclose double windows with filleted corners, while the central bay has a rectangular triple window with narrow side lights. The lintels above seem to be stone with incised designs, eared, rising to a shallow point. But the entablature is truly strange, comprising on the side bays three evenly spaced segmental arches with some kind of projecting finials and panels that match the curve of the arches. In the central bay, there is a more elaborately framed trefoil curve that suggests a triple arched Palladian design, but it is strange that that is not reflected in the window. The porch similarly has this trefoil shape, albeit with open spandrels, resting on thin columns. I can't actually tell the forms of the brackets from the images. The cupola seems almost oversize for the house, with curved frames around the tombstone windows and a balustrade above. The Midwest liked its fancy brickwork, but this is a very odd design. The house was torn down in 1928.

The Francis C. Sessions House, Columbus, OH

|

The Francis C. Session House, Columbus, OH. 1840, alt. 1862

From: Columbus Illustrated

|

|

| From: Illustrated History of Columbus |

The Sessions house, built for a banker on E Town Street, certainly started life as a Greek Revival house, given its 1840 construction date. But it appears that it was transformed into a fine Italianate residence in an 1862 remodel. The house was torn down in 1924 to make room for the current Beaux Arts Columbus museum. The house was a symmetrical plan villa, with a projecting central bay with a shallow gable. While the central bay was decidedly flat, the side bays were articulated with elaborate brick work which formed a thick set of quoins at the corners and recessed frames for the central sections of each bay. Whether these were part of the original house is unknown, although it would be very atypical for a Greek Revival house to have such fripperies. On the first floor, the sides featured rectangular windows framed by delicate fringed porches (with almost invisible balustrades atop), perhaps of iron (that wisteria really makes it unclear), while above, the windows had small wooden awnings with a fringe. The central bay had a recessed entrance with, again, a porch with triple arches and a rather weird set of three arches in the central span. Above was an iron balcony with fancy urns at the corners in front of a wide arched window with a bracketed wooden awning forming a Palladian form. Above, the cornice has a strong resemblance to the Baldwin house which survives up the street, with elongated brackets the break into strong s curves. These enclosed a pair of windows with concave corners, another reminiscence of the Baldwin house. The whole was topped with an octagonal cupola, with pierced s curve brackets, paired windows (also seeming to have concave corners), and a lacy iron cresting. All the bells and whistles abounded, with a conservatory and a whole other cube built on back. A shame it didn't survive, but it was replaced by an exceptionally fine museum building.

Monday, April 2, 2018

The Fernando Cortez Kelton House, Columbus, OH

|

| The Fernando Cortez Kelton House, Columbus, OH. 1852 |

The Kelton house, just a bit past the houses featured in my last post, is not only well preserved on the outside but within, as it is currently a house museum which has a substantial collection of the family's objects intact. It's an early design, 1852, and as such is a somewhat transitional symmetrical house that grafts some Italianate features, notably brackets, onto what is essentially a Greek Revival design with slim stone lintels over the windows and a fine stone, Greek Revival door. The house does feature an early Italianate roof design. Like most early Italianates, there is no strong entablature or heavy sculptural quality to the cornice line. The brackets here are of the s and c scroll type and have deep ridges. One unique quality about this house is the tiny, fine drops at the corners of the eaves, a feature that is strikingly uncommon in Italianate houses and one of the coolest features on the house. It's also nice to see the original roof balustrade at the peak intact; roof balustrades were once a ubiquitous feature of 19th century architecture. Unfortunately, once they rotted off they were rarely replaced, distorting the appearance of many a house.

Sunday, March 4, 2018

The John Crouse House, Syracuse, NY

This is a rather interesting design, demolished, from Syracuse, NY. It was built by John R. Crouse, a major banker in Syracuse, in the 1850s, and in 1904 became the law school at Syracuse University. Fronting on Fayette Park, one of the city's early planning and mansion districts, it would have had a rather over-landscaped Victorian park as its front yard. It was demolished in the 1920s. The house bears a striking similarity to the design of Henry Austin for the Willis Bristol house is New Haven, CT, particularly in its proportions. There it was a simple form with Indian architectural elements grafter on; here the same sort of design is interpreted in a Gothic mode. Following the symmetrical plan, like Austin's house, it featured a spare stuccoed facade, with a generous third story and long s scroll brackets, paired and without an entablature. The gothicism is restricted to the windows, as the porch is a rather typical design. Above each window is a simple Gothic molding with carved stops; each window is inset with a unique gothic tracery overlay, with intersecting pointed arches and foils in the tracery. The bay window to the side receives a similar treatment, with more traditional pointed arches. A low cupola, another Austin feature, topped the whole with large brackets. Note how the ironwork similarly matches the Austin formula. Though I could not produce an exact chain of influence, it is clear that Austin's plans, perhaps published or seen in person influenced this house. Other images can be seen here, here, and here.

Thursday, March 1, 2018

'Woodlawn' the Henry Howard Owings House, Columbia, MD

|

| The Henry Howard Owings House, Columbia, MD. 1840 Photo: Wikimedia |

Tuesday, January 30, 2018

The Emil S. Heineman House, Detroit, MI

|

| The Emil S. Heineman House, Detroit, MI. 1859 Photo: Scott Weir |

Saturday, January 27, 2018

The David Ward House, Detroit, MI

|

| The David Ward House, Detroit, MI. 1864 Photo: Scott Weir |

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

The Cyrenus Adelbert Newcomb House, Detroit, MI

|

| The C. A. Newcomb House, Detroit, MI. 1876 Source: Scott Weir |

Tuesday, January 16, 2018

The Francis Adams House, Detroit, MI

|

| Francis Adams House Detroit, MI. 1860s Photo: Scott Weir |

Thursday, December 21, 2017

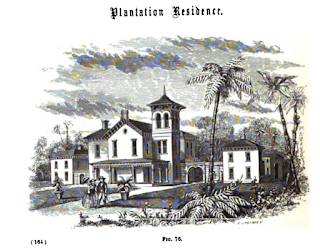

Sloan's "American Houses"

This is essentially Sloan's final big pattern book and is more influenced by other styles, particularly Gothic, rather than Italianate. Still there are a few Italianate plans. A nice feature in this work is the coloring of the illustrations and a greater presence of higher style Italianate designs rather than the more simple country and cottage designs. Several can be found in Homestead Architecture as well.

Design 2:

Design 2:

Design 3:

Design 4:

Design 5:

Design 6:

Design 8:

Monday, December 18, 2017

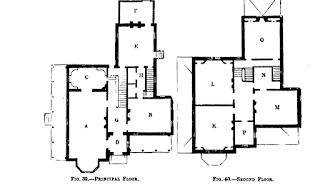

Sloan's "Homestead Architecture"

In 1861, Sloan published two more books of plans, his Homestead Architecture and American Houses. These are his Italianate designs from HA. In HA Sloan shows some changes from his earlier work, including a shift towards more simplicity in decorative details, the exclusion of high style European and exotic designs, and the greater use of Gothic detailing, higher pitched roofs, bargeboards, all on an Italianate frame.

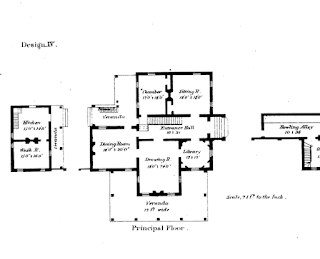

Design 4:

Design 4:

A rather elaborate towered design.

Design 6:

This is a variant on the typical three bay symmetrical Sloan design with a projecting central focus.

A hybrid Gothic/Italianate design. This reflects Sloan's recent experiments with Gothic Revival, as can been seen in the Asa Packer house.

Design 10:

Design 12:

This is a particularly massive, urban design, with quoins, a full three stories, and a paneled framing of tower elements, seen on his earlier designs.

Design 13:

A rather simple rustic design.

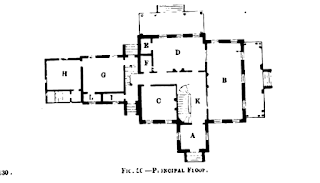

Design 15:

Design 22:

This is a rather unique house with an irregular stone exterior, a very Pennsylvania feature, very broad eaves, and the interesting displacement of the main entrance to the side, perhaps reflective of some of his work at Woodland Terrace.

The design for the Eli Slifer house in Lewisburg.

A rather new instantiation of the octagon design. Though in plan it closely resembles the plan for Longwood, the exterior could not be more different, with gables and verticality emphasized rather than expansive and exotic details.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)