|

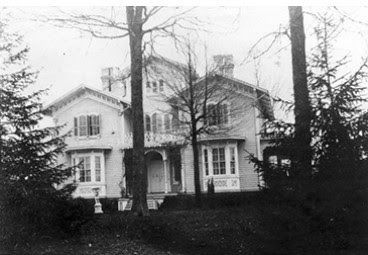

| The Henry Howard Owings House, Columbia, MD. 1840 Photo: Wikimedia |

A blog devoted to American Italianate architecture of the 19th century. This blog features architectural analyses of Italianate domestic buildings with images, and historical information. My plan is to show the varieties, regional vernacular of Italianate architecture.

Showing posts with label beam brackets. Show all posts

Showing posts with label beam brackets. Show all posts

Thursday, March 1, 2018

'Woodlawn' the Henry Howard Owings House, Columbia, MD

Wednesday, February 14, 2018

'Clifton' the Johns Hopkins House, Baltimore, MD

|

'Clifton' the Johns Hopkins House, Baltimore, MD. 1858

Photo: Doug Copeland

|

|

| Photo: Wikimedia |

A blog post shows detailed shots of the house and the interior during renovation, with great images of the stunning plasterwork, fine stenciled walls, and unique woodwork. The design of the tower, semi detached and connected by a low wing suggests strongly to me Osborne House, one of the UK's premier Italianate palaces:

|

| Photo: Wikimedia |

Sunday, February 11, 2018

'Locust Grove' the Samuel F. B. Morse House, Poughkeepsie, NY

|

'Locust Grove' the Samuel F. B. Morse House, Poughkeepsie, NY. 1850

Photo: Wikimedia

|

|

| Photo: Wikimedia |

|

| Photo: Wikimedia |

Sunday, December 17, 2017

The Eli Slifer House, Lewisburg, PA

|

| The Eli Slifer House, Lewisburg, PA. 1861. Source: otandka |

|

| Source: Bill Badzo |

|

| Source: Wikimedia |

Sloan published his design for this house in Homestead Architecture, as Design 33.

After serving as a religious institution for many years, the house is now a museum. On their website is a gallery of interior images, which indicate the house seems appropriately furnished for its period.

Tuesday, December 5, 2017

'Dunleith' the Robert P. Dick House, Greensboro, NC

|

Dunleith the Robert P. Dick House, Greensboro, NC. 1856.

Source: Greensboro Historical Society

|

|

| Source: NCSU Library |

Elevations:

Plans:

Details:

Another house is Greensboro that seems modeled on a Sloan design was 'Bellemeade' the William Henry Porter house (demolished). This is another manifestation of Design 9 from the Model Architect. This is an impressive symmetrical plan house in its own right, with an octagonal cupola and paired windows, as per Sloan's published plan. Where it differs is in the details. Unlike the plan in MA, the house has a rather elaborate, heavy cornice with a fringe and panels. The brackets are larger and heavier. And the ornamentation over the central triple window is unprecedented as an example of carpenter whimsy, with a design of fringes, and tassels that almost looks like a wooden manifestation of an interior cornice box. The porch as well, though it keeps the simple post design, has been gussied up with fringe.

|

| Source: Ginia Zenke |

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

'Alverthorpe' the Joshua F. Fisher House, Jenkintown, PA

|

| 'Alverthorpe' Jenkintown, PA. 1851 All Photos unless otherwise credited: HABS |

|

| Photo: Diary Sidney George Fisher |

The Joshua Fisher house, known as Alverthorpe (frustratingly misspelled as Alvethorpe in HABS) was built in 1851 for a prominent Philadelphia merchant and general rich guy. He was well traveled (Grand Tour 1832) and gathered an impressive historical and art collection at his home. Drawings indicate Notman designed the house and the formal gardens, and it remains one of his most impressive designs. Fortunately HABS documented the house before it was unfortunately demolished in 1937. Notman went all out for this commission, choosing the pavilion plan as his base and adding a tower to the side as well as an extension wing with a gabled pavilion and a particularly fine wrought iron porch, one of the most impressive pieces of wrought iron I've seen from this period. As we expect, Notman never puts a tower where one expects. Resisting the urge to play with polygons here, Notman constructed a cube that is three stories rather than the typical two, making the house far taller than usual. This height is balanced by the service wing, which corrects the vertical with horizontal balance. The façade is they expected fieldstone with brownstone quoins and trim.

The detailing on this house is ambitious to say the least. On the principal façade, Notman has turned the first floor into a colonnade with pilasters between the triple windows on the first floor and a large semicircular portico with a full entablature and large brackets. The whole is topped with a Renaissance balustrade. The main entrance continued the glass wall of the first floor with large windows surrounding the main entrance (the first glass curtain?). While the window surrounds are simple on the second and third floors (triple windows in the center bay, single on the sides), each window has a balcony that gives it extra weight. The cornice features not one but two sets of beam brackets superimposed, making for heavy cornice line. The tower is a sculptural masterpiece, with simple detailing on the lower floors that expands into rectangular triple windows with a heavy bracketed balcony above. The upper stage has triple arched windows with interesting brackets that curve out from the façade in a large c scroll, making it look like they almost organically grow from the masonry. Other interesting details are the porch on the right hand façade, which is an adaptation of a rustic Italian motif we will see at Fieldwood. The service wing with its gabled pavilion that has a triple arched window is especially charming, looking like a small monastery chapel. The wrought iron is amazing, as I already gushed. From the few interior views, one can see the house had an impressive amount of classical detailing. Coupled with the fine formal gardens, patios, urns, and sculptures, this house is the picture of a wealthy wonderland. All I can say is its a shame we can't enjoy this today.

Monday, April 11, 2016

'Hollybush' the Thomas Whitney House, Glassboro, NJ

|

| 'Hollybush', Glassboro, NJ. 1849 Photo: JasonW72 |

|

| Photo: Wikimedia |

The house was sold by the Whitneys in 1915 and promptly bought by what would become Rowan University as the president's house. It's well-known primarily because it hosted a Soviet-American summit in 1967 over the Six Day War. Interiors can be seen here.

|

| Photo: Wikimedia |

Saturday, February 7, 2015

'Fountain Elms' the James and Helen Williams House, Utica, NY

|

| 'Fountain Elms', Utica, NY. 1852 Photo: Wikimedia |

|

| Following Photos: mrsmecomber |

Interesting features of the house include thick brownstone moldings around the windows, fine rafter brackets typical of early Italianates, and blind arches (even in the chimneys). The thickness of the moldings on the second floor round headed windows gives the house a top-heavy appearance because of the simplicity of the bracket and cornices on the first floor windows. The Palladian window in the center is uncommon, but particularly unique is the Palladian configuration of the door with detached side lights. The porch and balustrades are dignified and Renaissance-inspired. Finally, the color scheme of this house is particularly historical and well conceived. Here, the stucco is painted yellow, while the trim is all a uniform brown to simulate the brownstone of the moldings. This house allows us to consider the effect of using simple and historically correct colors for an Italianate house.

|

| Photo: Mike Christoferson |

Wednesday, January 28, 2015

'Blandwood', the Charles Bland House, Greensboro, NC

|

| Blandwood, Greensboro, NC. 1844 |

Atypical for an Italianate house, this building lacks the usual play of round and flat headed windows that are usually found in towers. Similarly, the small size of the second floor windows is uncommon. The house also creates a strong sense of formality by the connection of the kitchen and side buildings with segmental arched arcades and simple pilasters. A folly like this is more common in English formal design than American. The interiors are well preserved, since the house was saved from demolition and now operates as a museum. A couple images below, selected from the NCSU page on the house, illustrate the elaborate interiors in their pre-restored state. Blandwood is a rare survivor of a fascinating early page in the history of Italianate design in America.

|

| Following Photos: NCSU |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)