|

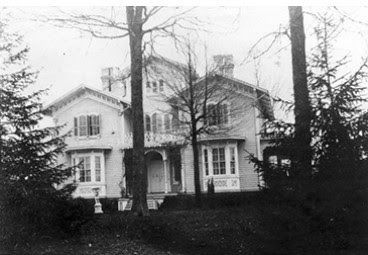

| Woodland Terrace, Philadelphia PA. 1861. |

Woodland Terrace is the finest collection of Sloan architecture that survives, in large part because it remains substantially intact (though there have been alterations over the years). Built in 1861 by Charles M. Leslie as a speculative development, Sloan designed a series of double houses on both sides of the street, five on the east side and six on the west side (a variation required by the intersection of the street by the diagonal Woodland Avenue. The terrace has two types of plan. The houses at the ends of the street have an

irregular plan, with towers (though these vary), while the houses in the center of the block follow a

symmetrical plan of four bays. The end houses following the irregular plan have a projecting pavilion with triple windows and a slightly recessed pavilion with two bays, with a further deeply recessed bay. The towers are placed to the side of the projecting pavilion and are deeply recessed. A porch extends to the principal recessed bay and the deeply recessed bays to either side. The main entrances for both houses are on the deeply recessed bays. The symmetrical plan houses have a central block of four bays and to either side there is a two story deeply recessed bay with a taller three story projection behind. A porch extends the full front. Some of the symmetrical designs have a cupola, but others do not. The main entrances here as well are placed in the deeply recessed side bays.

Sloan arranged the progression of houses with an eye to symmetry without creating monotony, an eye for large scale composition he demonstrated on

Pine Street. On the east side of five bays this can be seen best. The two end units follow the irregular plan, but while the northern house has a stubby gabled tower with two rectangular windows, the south house has a full hip roof tower with triple arched windows. The three central units follow the symmetrical plans, but units two and four do not have cupolas, while the third unit in the center has a large cupola divided between the two houses with four arched windows, marking the center of the block and creating emphasis. Sloan has masterfully balanced the composition with regularly spaced focal points in units one, three, and five and provided a deemphasized background in units two and four. This design was somewhat complicated in its repetition on the west side, since the even number of houses prevented the central focal point. Sloan handled this by putting cupolas on both houses in the center, three and four, maintaining a central focus. The most unfortunate loss is the demolition of half of the final unit on the west side, depriving that section of its grand punctuating tower.

All the houses were designed consistently, with facades of irregularly cut brownstone (a Pennsylvania specialty) divided into three floors, with rectangular windows on the first two floors with bracketed hood moldings, a stringcourse between the second and third floors, with arched windows on the third floor and paired brackets. The brackets are of the

double s scroll type. The principal facades feature fine cut brownstone, while the sides are made of irregular fieldstone. The porches are simple, with small brackets, sinuous ogee curves, and thin paired posts supporting the porch (lost in a few examples). That is the base design that forms the stylistic unity between each unit. Originally, the houses would probably have featured a very consistent paint scheme, avoiding the jarring effect when owners paint different sides of a unified house different colors, divided in the middle. The entire ensemble was photographed by

HABS.

The East Side of the row:

The West Side:

Sloan also designed the nearby Hamilton Terrace at 41st and Baltimore in 1854. Little of this survives.

Another double house of interest, sadly demolished, one block over from Woodland Terrace at 435 S. 40th Street where the transit station is now. The house featured two towers surrounding a central block of paired windows with wooden awnings, balconies, and an elaborate arched porch with fine jigsaw work. While not attributable as Sloan, and perhaps a bit too fanciful for him, nonetheless, it displays Sloan's influence in its fascination with varied massings, differing volumes, and variety in design, producing a balanced symmetry.

This same design, certainly by the same builder could be seen rendered in Second Empire on Baltimore Avenue:

A final Italianate of interest in a very Sloan like style could be found across the street from the 40th street houses, at 440 S. 40th Street. It looks like it might have been a triple house by the number of entrances. The house follows the pavilion plan, though somewhat asymmetrically. A large pavilion on the left featured a two story bay window (with a tower to the rear), while the left hand pavilion was two bays, evenly spaced. The central four bays had a large porch running across the front. The quoins, the string course, the side placement of the tower, and the simple porch are all highly reminiscent of Sloan's designs nearby on

Pine Street and demonstrate his influence in the area.