|

| John Smith Photography See other posts for photo credits. |

1. A mostly uniform cornice line, set at two and a half stories, as can be seen in the image above. While the cornices themselves display a wide variety of forms, brackets tend to be smaller and closely spaced, while entablatures are simple and mostly paneled. When windows enter into the design, they tend to elongate the brackets to make a strong frame for the window.

2. There is a strong horizontal emphasis provided by heavy string course moldings that clearly divide floors. Additionally, windows may be connected with horizontal moldings bands. Vertical emphasis is achieved by the framing of the facade and its elements with pilasters, quoins, and changes in volume to create complexity in an otherwise simple facade.

3. The favored material is primarily stone rather than cheaper brick. The use of stone allows the houses to have a more European and wealthy feel to them. Sometimes the stone is rusticated to delineate floors. Side walls of these houses are unimportant, and therefore the ornament and stone stop on the sides.

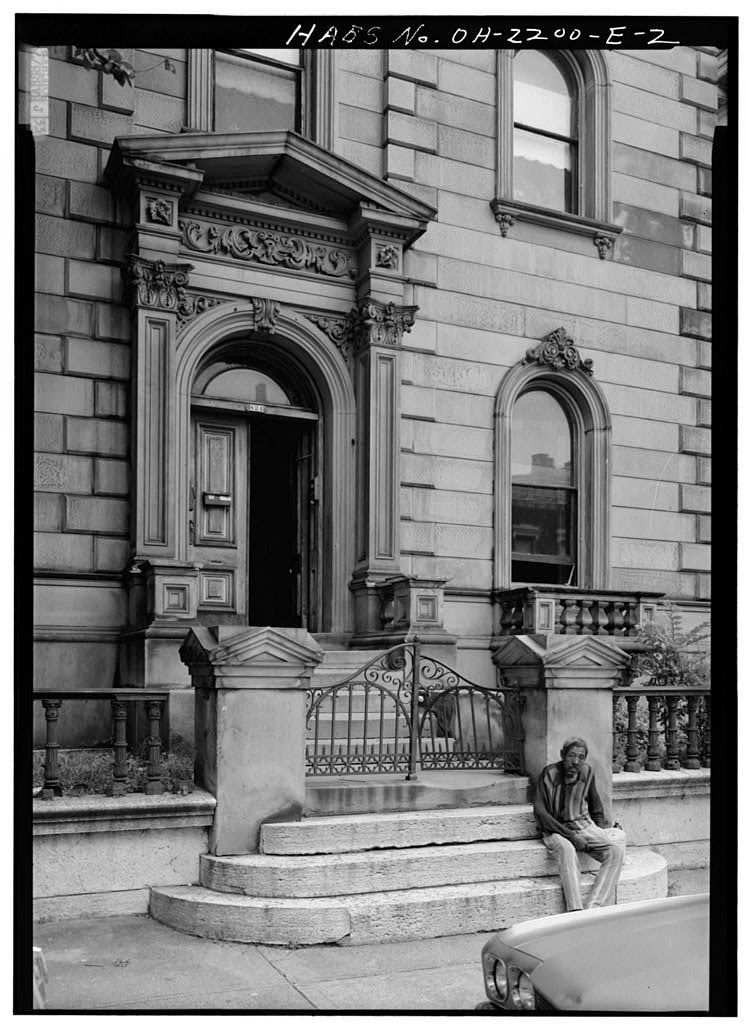

4. Ornament is not overwrought. Primarily, it consists of heavy, thick moldings, carved panels, and paneled keystones. The one elaborate feature is vegetal and rococo carving, an expensive mode of ornamentation whose use demonstrated the builder's wealth. This carving, however, is confined to specific architectural areas, window crests, panels, doors, and cornices.

5. The favored shapes for windows and doors are overwhelmingly arches. Houses often have a combination of round arched and segmental arched windows. Door surrounds are typically fancy, with several houses having an engaged arched surround:

6. House plans tend to be either symmetrical or rowhouse types.

7. Finally, there is a uniformity achieved by fencing to the street. The connected stone retaining walls and newel posts framing the iron fencing gives the street a connecting base that connects all the houses. Similarly, balconies of either iron or stone create variation in the streetscape.

All in all, Dayton Street provides a textbook example of unified Anglo-Italianate design in America. Other neighborhoods of a similar character could be analyzed in a similar way, and, although there would be regional variations depending on local taste, nonetheless, a house in Cincinnati, Baltimore, or New York would resemble others elsewhere. Despite not being a common style throughout the country, the Anglo-Italianate idiom shared common features that connected it and wealthy families, with their like around the urban landscape of the 1860s and 1870s.

.tif%2B-%2BCopy%2B-%2BCopy%2B-%2BCopy%2B-%2BCopy.jpg)

.tif%2B-%2BCopy%2B-%2BCopy.jpg)

.tif%2B-%2BCopy.jpg)