|

| The Joseph Harrison House, Philadelphia, PA. 1856. |

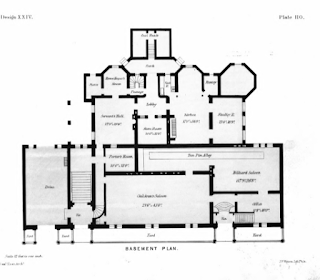

Sloan designed the Joseph Harrison house in a prominent location in urban Philadelphia, on Rittenhouse Square in 1856. Harrison was an extremely wealthy railroad inventor and builder who was responsible for building a large portion of Russia's 19th century railroad system. Harrison bought an entire side of Rittenhouse Square in 1855 and set about building his house facing the square and also designing a series of row houses behind, filling the block. Considered one of Philadelphia's most extravagant houses, it housed an art collection that would form one of the core collections of the Pennsylvania Academy in one of its wings. The house was demolished in the 1920s.

Architecturally, the house does not follow a typical Italianate plan, and may have reflected a design that impressed Harrison in St. Petersburg, though which house this would be is anyone's guess. The house has strong European influences; it is completed in masonry with strong quoins (the whole is basically strong Anglo-Italianate in finish, and the central pavilion block has no entrance in the center of the façade, as one might expect. Rather, we find entrances placed to the sides, similar to how some European urban houses contain a building entrance and a carriage entrance both disguised as doors (here the carriage entrance is placed under the left hand pavilion). Additionally, there are no high stoops here; the stairs that elevate one from the entrance level to the principal floor are placed inside. The finish with balustrades, attic, and rustication is a perfect example of Samuel Sloan's more sophisticated taste having free reign.

The house is, from the front, a large symmetrical cube of three stories and three bays set on a high basement. The façade is stone, with quoins. The basement is rusticated with segmental arched windows. On the first and second floor, three tall windows with depressed arches each contain Venetian tracery with a small gothic column at the joining. The windows are framed only by a very deep molded surround that casts a strong shadow. The third floor varies the design, with small paired arched windows, a device seen in other Sloan designs in which the third floor breaks out into a series of grouped arched windows. The whole has an entablature without brackets with a tall attic railing above, which was carved with Harrison's monogram. The main entrances flank the central block, tall arches with massive doors and balustrades. The side pavilions are the real innovation here, not recessed or subordinated to the main façade, with a strong rusticated base and a smooth second story with a projecting oriole window. The pavilions balance the austerity of the central block with a richer texturing that allows them to hold their own and maintain themselves as visual focus points in relation to the massive bulk of the main block. The whole had a unique stone fence, almost Moorish or Gothic in design, running around the front of the property.

The rear of the central block differed significantly from the austere front. Two bay windows that ran the full height of the building connected by a two story porch with strong arches, Gothic-esque posts, and interlacing tracery. It almost has a Moorish air with the grand octagonal greenhouse and overlooked an impressive garden. This was probably one of Sloan's greatest accomplishments; it's unfortunate it didn't survive. Sloan published his plans, elevations, and details in his publication of 1858, City and Suburban Architecture.